There’s been some momentum in recent years for curling to standardize game length to eight ends. The current protocol in curling is for national and provincial championships and associated qualifying to be ten ends and all other games to be eight ends.

The debate to keep 10-end matches mostly comes down to the fact that the better team will more often win while the case for 8-end games is that they are more concise. If you value fairness more than entertainment, you’ll probably be partial to 10-end games and vice versa.

As Brad Gushue said in the linked piece above,

From a pure television and marketing perspective, I think eight ends is the way to go. From a pure curling perspective, I think 10 is a better test of who the better team is.

Since I’m not one of the best curlers in the world, I lean towards entertainment and prefer 8-end games. Ten-end games might only be a half hour longer, but if you want to watch three draws in a day, that starts to add up. I’ve never played in a 10-end game but 8 ends is plenty for me. I love curling but at some point enough is enough. I love Golden Grahams, too, but you don’t see me having four bowls of it for breakfast. One for breakfast and one for dinner is just fine.

Mind you, if I was Brad Gushue I’d want my games to be 10 ends. Actually, I’d want to turn back the clock to the 1924 Olympics and make them 18 ends. If you have the best team in the world, you want as many shots as possible to prove it. But we can test the fairness hypothesis with data. And the results might surprise you.

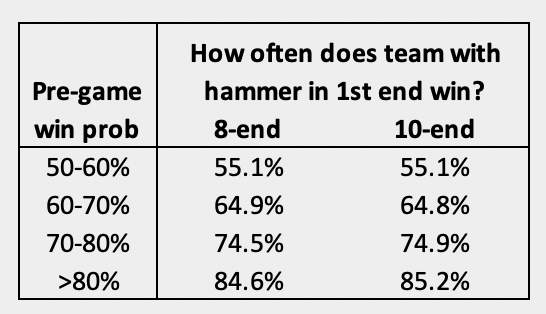

One of the benefits of creating a rating system that makes probabilistic predictions is that we can use it to establish which team is the favorite before every game. It turns out, 10-end games are won by the favorite more often than 8-end games. (All figures cited going forward are from games over the past three seasons where both teams had a rating of 10 or better entering the event. Basically, they were top 100 teams.)

Over the past three seasons, the favored team won 64% of the time in an 8-end game and 67% of the time in a 10-end game. It’s a significant difference but not all that noticeable to the average human. We’re talking an additional upset every 30 games. Which, by the way, I would propose is a feature of 8-end games. Curling could use a few more surprises, and besides, you clearly don’t want the best team winning too often. Then there would be no suspense. (Though I get why a provincial association would not be thrilled with a system that makes it more likely that its best team doesn’t represent the province at the Brier or Scotties.)

I think that 3% difference is small enough to alleviate any concerns the best teams might have about going to 8-ends, but there’s a little more to it than that. Nothing is ever simple when interpreting curling data and just looking at the raw win percentages doesn’t tell the whole story. In fact, that 3% difference is actually a mirage.

If you go to the analytics page on CurlingZone you’ll see that the team that gets hammer to start an 8-end game has won about 62% on the men’s side and 59% on the women’s side over the past four-plus seasons. But how does that compare between a 10-end game and an 8-end game?

Here again is where a good rating system can help us. Those hammer winning percentages are a mish-mash of a lot of games and hammer winning percentage is actually a function of both how good the teams are and how much better the favored team is. We need to control for those things to do an apples-to-apples comparison.

Also, those numbers are influenced by the fact that the better team usually starts with hammer. In an 8-end game, the better team has started with hammer 55% of the time and in 10-end games, that number is 58%. Why the difference? I’m not sure, but my guess is that there’s more “structure” in events that have 10-ends.

First-end hammer can be determined by coin toss, draw shot challenge, or playoff seeding. I think it’s the last thing that makes a difference in 10-end games. I would guess the seeding of the playoff round is more reflective of team ability in 10-end events. Events with 8-ends often feature smaller pools in round robin play, or are triple-knockout format, which results in seeding in the playoff being a lot more random relative to team ability.

The coin toss is less of a factor since most serious competitions do not use a coin toss these days, but to the extent that they do (and actually the events in Switzerland this season used it for the first draw) they are solely the domain of 8-end games. Even draw shot challenge might be won more often by the better team in 10-end games since the ice is probably better and more practice time may be available, removing factors which could help the worse team.

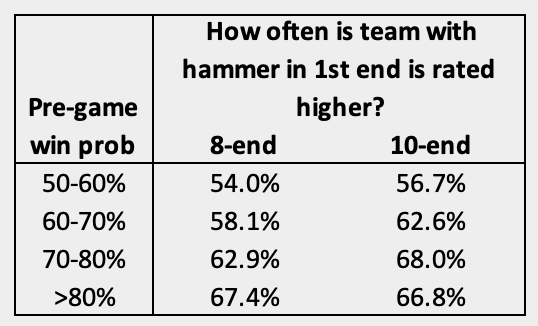

For posterity, here’s how often the best team gets hammer based on how much they were favored by in both 8-end and 10-end games according to my ratings:

For example, if a team is a 70%-80% favorite heading into a match, they have started with hammer 63% of the time in an 8-end format and 68% of the time in a 10-end format. There’s a clear signal across all matchups that the better team is more likely to start with hammer in a 10-end game. And we know that the team starting with hammer has a better chance of winning.

Therefore, to do this analysis properly, we can’t just control for team quality. We also have to control for whether the favorite starts with hammer. Once we do that, there’s practically no difference in win percentages for favorites in a 10-end game compared to an 8-end game.

Once you know who has hammer, there are hardly any more upsets in an 8-end game than there are in a 10-end contest. And that should be reassuring if the curling world puts the 10-end game in the rear-view mirror.

I think curling traditionalists probably want to stick with 10 ends for major championships. There’s a sense any change to a shorter game is not being made to improve the competition but rather to appease TV or to try and lure new fans who are less willing to invest 3 hours or more to watch a single game.

But the data shows that there is nothing to be gained from a fairness standpoint by playing 10 ends. Yes, there is more curling, and that’s never a bad thing for those obsessed with the sport. But those additional ends don’t impact how often the better team wins. And if we don’t have to sacrifice fairness while also growing the sport’s audience, it sounds like a win for everyone.

Now, it is certainly an interesting mystery as to why a longer game wouldn’t produce fewer upsets. One would think it should but that’s a more complicated investigation that will have to happen at a later date. [music plays] As Dr. Katz would say, you know what the music means. Our time is up.