If you eavesdrop on a discussion of whether it’s better to be one up without last rock in the final end or down one with hammer, everyone agrees that it’s better to be leading. The numbers say teams win about 60% of their games when up one without last rock in the last end, so there’s really no reason to carry on the conversation beyond that point.

But there are aspects of this situation that invite more investigation. In this piece, I’ll look at two things:

In order to assess why being up one without hammer is the advantageous situation, let’s break down the situation into its component cases. When you’re up one, there are three possibilities for the final outcome: you give up 2 or more and lose in regulation, you give up 1 and go to an extra end, or you steal 1 or more and win in regulation.

So here’s what has happened in all events of level 10 or greater (men’s or women’s) over the past four-plus seasons. (For an explanation of levels, refer to my previous post.)

cases W(EE) WP Result allow >1 1033 (32.3%) loss allow 1 1136 836 26.1% tie->win steal 1035 32.2% win total 3394 58.3%

There’s a convenient symmetry here in that there have been almost the exact same number of wins and losses in regulation. What tips the scale is that the leading team will have last rock in an extra end, if needed, and it gets the win in about 74% of those cases.

Obviously all of those components change a bit depending on the skill level of the participants, and determining how they change is an interesting (and complicated) investigation of its own. (Based on some work I’ve done so far, being up 1 without hammer is slightly more of an advantage at lower levels of curling than it is for elite curlers.)

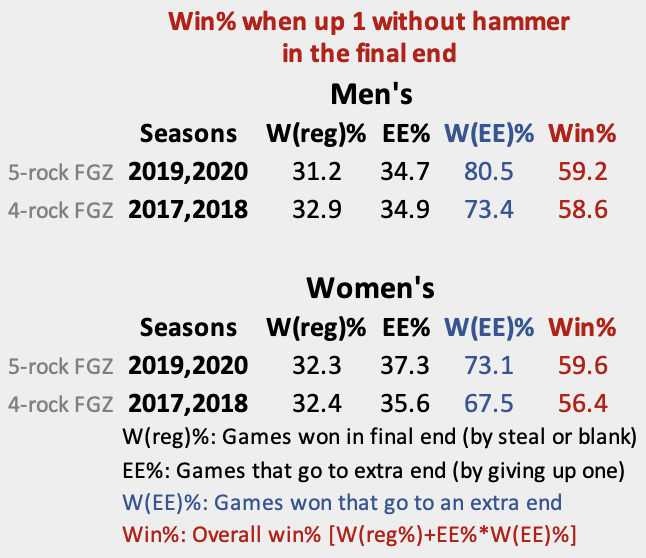

I haven’t seen much work on how the five-rock rule has impacted the game, so let’s take a look at how the numbers have changed in the last two years. Again, the following data includes events at level 10 and above.

Win% up 1 without hammer in the final end of regulation

Seasons Men Women 2019,2020 59.2% 59.6% 2017,2018 58.6% 56.4%

There’s been about a 0.6% increase in winning percentage for the men and a 3.2% increase for the women since the five-rock rule came into play. End of discussion, right? Well, hold on. Even though there’s been a change in win probability since the five-rock rule was adopted, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the five-rock rule is the reason for the change.

We know that teams with hammer have gotten better at scoring in the extra end in recent seasons. Maybe that’s the reason for the improvement. In fact, it’s entirely possible that five-rock rule is actually hurting the team up one without last rock, but that the improvement in extra-end performance has more than made up the difference. So let’s break down those win percentage numbers further.

(Season is meant to refer to the year in which the curling season ends. So 2019 means the 2018-19 season. Also, I’ve removed Grand Slam events from the 2017 and 2018 seasons as they were played with the 5-rock rule.)

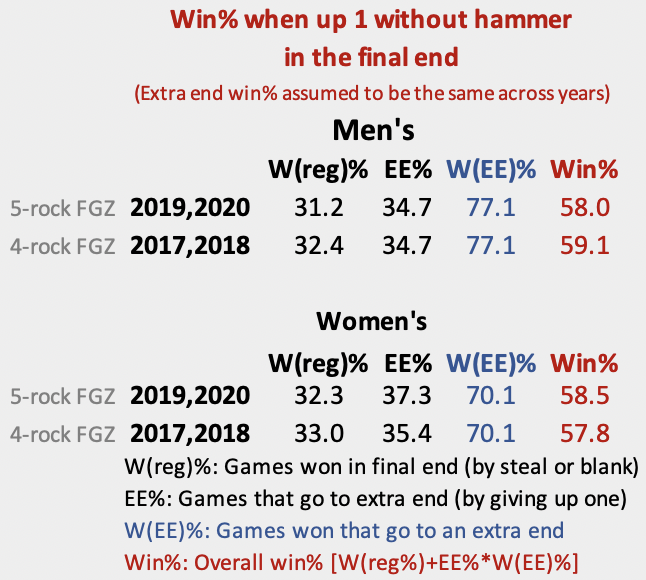

We do see that winning percentage with hammer in the extra end has increased substantially for both men and women. And that trend doesn’t figure to be related to the five-rock rule. One way to remove the effect of that is to make extra-end winning percentage the same for both the four-rock seasons and the five-rock seasons. We can use that to compute a theoretical winning percentage in these situations. If we use the average extra-end winning percentage over the entire four-season sample, our numbers look like this:

The five-rock rule doesn’t appear to have had any significant effect at all. If extra-end conversion rates would have stayed the same, we would have seen the team up one without hammer win slightly less often in the men’s game. On the women’s side, that 3.2% improvement in the raw data drops to just 0.7% when removing the effect of extra-end improvement. Not to get geeky, but the differences aren’t statistically significant. There’s an 80% chance the difference in the women’s percentages are due to randomness.

Basically, if the five-rock rule has caused a meaningful change in the up-one-without-hammer scenario, the difference is so small that we need more data to confirm it. A lot more data. There are about 800 cases in each sample so we already have plenty of data, but it’s still not nearly enough to detect a difference.

For all practical purposes, the five-rock rule hasn’t had an impact on the up-one-without, down-one-with dynamics. It’s better to be up one without hammer and given the improvement in converting the extra end, it’s getting even more advantageous with time.