The reigning women’s world champion, Team Tirinzoni, is competing in this week’s marquee event, the Adelboden International. The twist is that the event is a men’s event. As of last weekend (well, and still as of now), the team list on the event’s web site listed the 15 men’s teams and a ‘special team’ which I assumed would be a team made up of local politicians when I coded up the monte carlo simulation for the triple-knockout format. I more or less gave the proposed opponent for ‘special team’, Yannick Schwaller a first-round bye in the calculations.

But it’s great news that Tirinzoni is participating. It fills out the 16-team bracket and does so with a team that is better than some random men’s club team. Of course, it provides a bit of intrigue as well. What’s interesting is that the bracket is basically seeded. Strictly speaking, there are no seeds listed on the bracket, but in reality the bracket is constructed with team ability in mind. Schwaller is the one-seed, followed by de Cruz, van Dorp, and Retornaz. And I could go through the entire bracket for the remaining teams but will spare you that.

With Tirinzoni playing Schwaller, Tirinzoni is essentially the 16-seed. That doesn’t seem fair to either team in that match-up. Surely, Tirinzoni isn’t the worst team in the draw. It raises an interesting question without an easy answer: If you were the drawmaster where would you seed Tirinzoni in this event?

Before I touch the third rail of sports analysis, I must say a couple of things. It is refreshing that nobody in curling is really obsessed with two things that a certain segment of the basketball community is obsessed: how women would do against men and amateurism. (Go get those sponsorships, kids!)

Now I’m sure in the dark corner of a curling club somewhere, it’s been debated how the best women’s team would do playing the club champion. Nothing productive really comes from a public discussion of that sort. The purpose of what follows is rooted in the fact Yannick Schwaller is no longer getting a bye on Friday and I’d like to know how much of a non-bye he is getting in order to compute his chances of winning.

This also provides an interesting foundation to learn something. Because the top women’s teams rarely play the top men’s teams, we are up to our own devices to solve this problem. We need to find a measure that defines a team’s ability independent of the skill of its opponent. If we could do that, we could assess the ability of any team in the world, regardless of league or location or gender or age.

Unfortunately, that stat doesn’t really exist. I suppose if we had a lot of data from the free throws of curling, draw shot challenges, that would be close. One of the neat things about Switzerland owning the world curling scene so far is that SwissCurling publishes DSC data for its events so that will be something to dig into down the road.

Still, the DSC strictly describes one’s skill in drawing. To be successful, a team has to be great at drawing and hitting and being excellent at one doesn’t necessarily mean being excellent at the other. We’d also need a lot of DSC attempts to start showing meaningful differences between good and great teams.

Limited to data from games, I’m going to nominate a team’s winning percentage when it has hammer in the last end of a tie game as the most opponent-proof stat. The goal is to keep the house clean and if a team is able to play tick shots and peels and can reliably draw to the four foot, it doesn’t matter who they’re playing, they’ll be winners an awful lot.

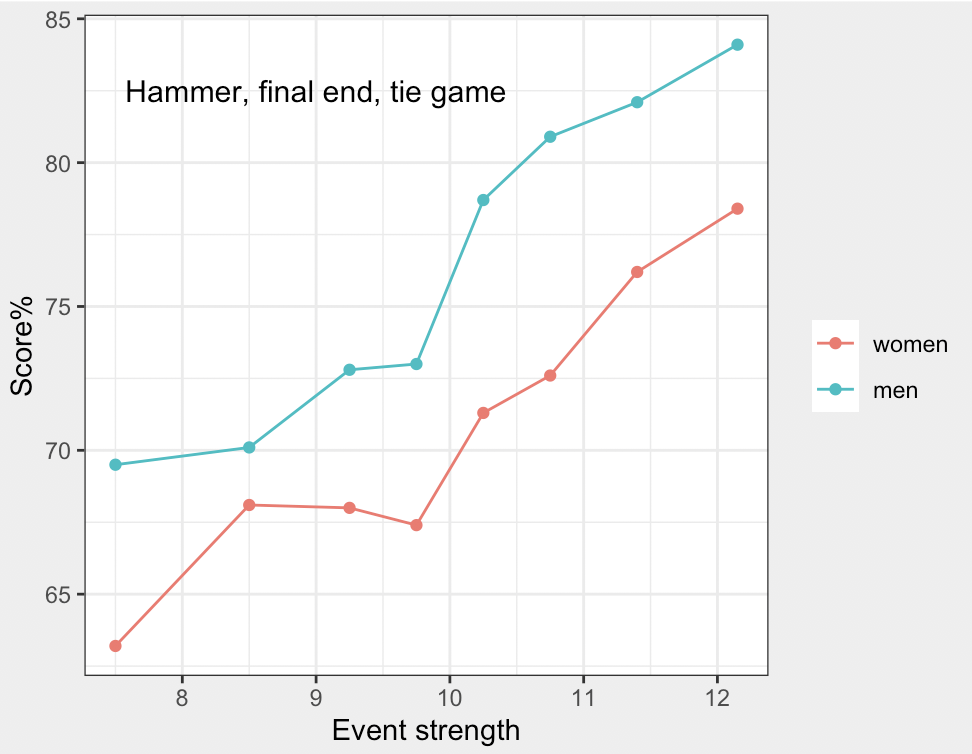

In order to judge team and opponent strength, I’ll use my ratings to get the average team strength for each event over the last five years. We can then separate events by their strength and look at hammer conversion in those events. We are going to look at the cases where the game is tied in the final end – either an extra end or the last end of regulation – and see how often the team with last rock scored.

Here’s the table of data based on the last three seasons:

Field

Strength Women Men

<8.0 108-63 63.2% 305-134 69.5%

8.0-9.0 339-159 68.1 511-218 70.1

9.0-9.5 149-70 68.0 390-146 72.8

9.5-10.0 308-149 67.4 466-172 73.0

10.0-10.5 434-175 71.3 483-131 78.7

10.5-11.0 331-125 72.6 262-62 80.9

11.0-11.75 244-76 76.2 147-32 82.1

>11.75 105-29 78.4 111-21 84.1

This data deserves more than monospaced fonts. Here it is in graphical form:

Obviously, if an elite team is playing a group of toddlers, they’ll win 100% of the time when tied with hammer. How the toddlers even got to that point in the first place is the bigger story, I suppose. But this chart indicates that great teams convert more often against great teams than good teams convert against good teams. Which supports the idea that the quality of opponent doesn’t matter nearly as much as the quality of team with hammer in these situations.

If hammer conversion in sudden-death were a perfect proxy for skill, then from eyeballing the gap in final-end hammer conversion, the women’s ratings are something like 1.5 to 2 points behind the men’s. That would put Tirinzoni in the 40’s in the men’s rankings.

But I’m a little skeptical of these numbers. For one thing, this method would make Anna Hasselborg like the 15th-best men’s team. And if the world’s best women’s team was that good, I think we’d see a lot more cases of the women playing the men. Who wouldn’t pay a few bucks to see Hasselborg match up against Matt Dunstone if it was a coin-flip game?

Last-end hammer strength isn’t a perfect proxy for team skill probably because the opposing team does have some influence on this. Even the best of the best occasionally make a mistake with hammer, and then it’s up to the non-hammer team to make them pay. Thus a 78% conversion for elite women against other elite women may turn into something like 72% against elite men. That puts the ratings difference in the 2.5-3.0 range and makes Tirinzoni around the 100-120th best men’s team (and Hasselborg around 50th). For now, we’ll consider this our best estimate, which gives Team Tirinzoni about a 1-in-150 chance of winning the event. As always, we’re prepared to be wrong.

The good news is we’ll get 4-6 games of Tirinzoni against a wide array of competition, so we’ll know a lot more by the end of the weekend. And given that international curling has been confined to Switzerland, this situation may come up again.

An interesting footnote about the extra-end hammer is that its value has increased in elite events in recent seasons. Back to the monospaced fonts!

Season Men Women 2020 84.1 77.4 2019 85.3 75.3 2018 77.0 71.2

I would imagine the increasing skill in executing the tick shot is the driver here. Regardless of the reason, there’s a much greater incentive to avoid being tied without last rock going into the last end. Teams should be selling out more often to get their deuce when down one. Even the best teams are mostly powerless to overcome this situation. By the way, special salute to Kevin Koe who has converted all 26 of these situations over the past three seasons. Rachel Homan leads the women’s game by converting 29 of 32 (.906) such situations. Yes, the 2019 Scotties loss to Chelsea Carey was as stunning as you thought it was.

Tirinzoni herself has gone 27-7 (.794) over the past three seasons when tied with hammer in the final or extra end. Should she find herself in that situation against Yannick Schwaller, her chances of winning may not be quite that good, but she’d still be a pretty clear favorite.